『アイコンとして地域に根付く建築』

1「背景」

田園風景が広がる京都府京田辺市は人口63080人(24533世帯)の小さな規模の町で、京都、大阪、奈良の3都市から挟まれ、どちらの市街地へ行くにも電車で30分程度要する地域である。

この地域にはギャラリーはおろか、アートに関する施設や地域住人が集える解放された建物はほとんどない。

クライアントのご夫婦はこの土地で30数年間、中学校と小学校の教師をされ、退職を機会に、自らが培った地域との関わりを活かした施設を作りたいと考えた。

そこで、多くの教え子や地域住人が日々の成果を発表し、集える建築を望んだ。

設計にあたり、当初はギャラリーという用途に特化することが、明快で地域に対して理解されやすいのではないかと考えた。

しかし、周りの都市圏と違い、人口の少ないこの地域では、何かに特化した建築を作る事は建築の実働時間を最大限活かしきれないため、地域住人に親しまれるような建築にはなり難いと判断し、様々な用途を包含できる建築を目指す事になった。

結果、児童図書館/ギャラリー/ミニコンサートホール/懇談会場/レクチャールームなど、様々な用途に対応できる建築になった。目的も用途もはっきりと決まっていない建築としてのあり方を模索する中、建築自身が地域のアイコンとなり得るようなものを目指していった。そして、「はっきりと何々をする施設」という認識ではなく、地域の人々に「何か楽しいことが行われる場所」という認識をもたれるよう目指した。

毎回、様々なイベントが行われる予定だが,既に行われたイベントでは老若男女を問わず、多くの人々が京田辺市内や周辺の地域から集ってくれる。

我々の予想以上に、短期間に多くの方々が口伝いでTANADAピースギャラリーの噂を広げてくれ、毎回来客数を増やしている。

つまり、都市圏外で公共的な性格を持つ建築を設計する事は、建築が地域住人の要望する様々な用途を受け止められる包容力のようなポテンシャルを持つ事が必要であると再認識させられた。こうして、この地域のアイコンとして残り続け、地域をキャラクタライズしてくれることを期待する。

2「リフォームではなく、敷地の更新」

この敷地にはもともとセキスイハイムのユニット住宅と日本家屋の別棟がその南側に建っていた。

生活の拠点はユニット住宅の東側半分にあり、西側半分は物置となっており、ほとんど使われないせいか、躯体の損傷もひどいものであった。

別棟も来客時の対応に使う以外、生活の拠点はなかった。

また、別棟へのアプローチは整備されておらず、各棟が敷地内で正常に機能しているとは言い難い状況であった。

そこで、今回の計画では、ユニット住宅の西半分を取り壊し、敷地内に三棟目の建物を新たに計画することになった。

これは、クライアントの要望でもあるギャラリーと居住空間をハッキリ分ける事で、他人にも貸し出しやすいということにもリンクしたことである。

残された既存ユニット住宅にはキッチン・浴室・洗面・リビングルーム・寝室などの居住空間が存在し、ギャラリーとは屋外通路をはさんで行き来が可能になっている。

前面道路からみると既存ユニットとギャラリーが並列に建っており、前庭に面した既存ユニットの浴室とトイレもギャラリーの一部として扱っている。既存ユニットの外壁は一文字張りで仕上げ、ギャラリーとの色味を合わせながら質感を変えることで、新旧の対比を表現している。

また、前庭には大きな庇がかかっており、既存ユニットとギャラリーをその軒下の空間によりつないでいる。

ギャラリーを作り、外構の整備を含んだ敷地の更新を行うことで、別棟もその機能を取り戻し、三棟の建物がインタラクティブに関連し合うことになった。

この敷地の東側には国道が通っており、そこから既存ユニット住宅を臨むことができる。

そこで、車通りの多い国道からの視線を考慮し、既存ユニット住宅がこのギャラリーの看板となることを意図した。

この地域には比較的少ない構えを持ち、白い箱状の建築となることで、国道を道行く人々の視界に突如真っ白な建物が飛び込み、そこに何かがあると意識を傾けることができると同時に、地域に対するアイコンとしても成立し得ると考える。

3「シーンから空間を造る」

様々なことができ得る建築を求めたため、その時々に起こるシーンの想定から始めた。そして、シーンの断片を集合/編集することにより空間を作れないかと考えた。

様々なプログラムが存在し、老若男女が集える空間で展開されるシーンを具現化するため、映像の設計図を描いた。

それは例えば、

壁や床にランダムに展示された絵画や彫刻を眺めている人々。

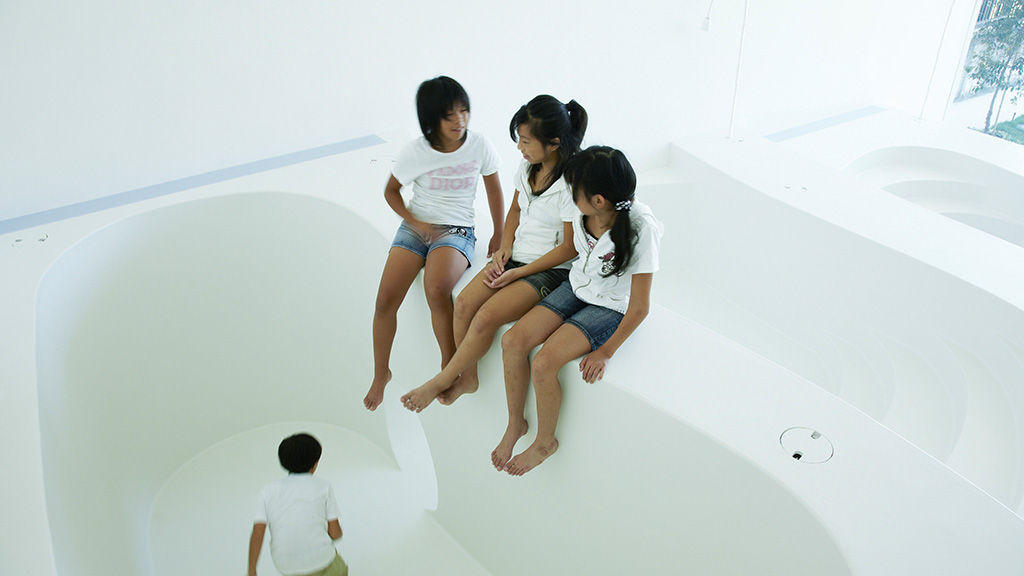

本を読んだり、鬼ごっこをしたりする子供たち。

その様子を見ながら、井戸端会議をする母親の集団。

のんびりと茶話会を楽しむお年寄り。

ワークショップに取り組む地域の人たち・・・

など、様々な想定したシーンが相互に関係し合うように空間に配置していくうちに、床に起伏を作ることが、空間に多様なプログラムを発生させ、想定した幾つものシーンを形にできることに気づいた。

更に、それら生じたプログラムに関して、各々に見合ったボリュームを与えていったところ、それは棚田のような形状へと辿り着いた。

作り手が建築を通して、そこでのプログラムを想定し、相互的に関連づけていくことで、使い手が想定以上のプログラムを多彩に想像することができる。

また、その建築での多彩な体験によって、記憶の中に空間が残る事で、地域をキャラクタライズすることへの試みでもある。

ギャラリー正面には小学校が建っていることもあり、多くの小学生が学校帰りに毎日のように遊びにくる。このギャラリーには、公園のように特に遊具がある訳ではないが、子供たちが自ら遊びを創造する光景が広がる。

また、一般的なギャラリーのようなホワイトキューブとは全く異なる内部空間のため、作家にとってここで作品を展示するのは非常に難しいであろうと元より考えていた。このギャラリーだからこそ出来うる表現方法が必要になってくるとともに、これまで、どのように空間を捉えながら作品を作ってきたのかという点を問われることにもなり、作家にとってある種の挑戦の場としても展開していくことを期待する。

Architecture as a Community Icon

A 30-minute train ride out of Kyoto, Osaka or Nara will take you to the peaceful agricultural town of Kyotanabe. In a few minutes’ walk from the station you will find the Tanada Piece gallery, the town’s first and only public art gallery. It is also the town’s only community building.

The clients, longtime residents and former school teachers of Kyotanabe, had a dream of creating a way of connecting their neighborhood by building an art gallery where they could exhibit the works of former students.

At first, we considered how the new building would function as a gallery in that region. We could not approach it in the same way as we could do with a gallery located in a bustling city. It would not have an ability to stay open late and the population of the region would not allow the gallery to be constantly busy. To increase the affectivity of the new space we decided that its function should not be limited to that of an art gallery but rather extend to that of a community centre, allowing for multiple functions. We extended the program to include, as well as gallery space, a children’s library, a small concert hall, a casual gathering space, and a lecture room. Following this, it was our desire for the gallery to become an icon of the local community: a place which function is not entirely set but becomes a place where community members can gather and relax. As the knowledge of Tanada Piece gallery has spread from person to person, several events have taken place there, attended by both young and old. We strongly believe that architecture should provide the needs of its community. We saw this in a more serious sight while designing for Kyotanabe due to the absence of any other community buildings. Our dream is that this gallery will last and begin to characterize the local region.

It is situated on the proposed site were the clients prefabricate house and a Japanese style house. Neither of these served as an effective working condition. The westerly half of the clients’ house was badly damaged, used only for storage and the pan-handle entrance to the Japanese house was inaccessibly cluttered with debris. The westerly half of the house was then demolished and, in its place, now stands the Tanada Gallery. It is separate from the house except for one small door that leads between the two. A visual connection between house and gallery was created by refinishing the house in white colored steel paneling to match the white of the gallery. The texture of the steel, however, differs from that of the gallery so as to distinguish old from new. The space created by the large roof overhang of the gallery continues along the side of the house further connecting it to the gallery. Along the east side of the house runs a main street. If one approaches the gallery from the south, the restored house, now in clean white, attracts residents to the new public venue. Access to the Japanese house behind was also restored so as to create three buildings in relationship with each other where the two had stood before.

To generate a design for the interior we envisioned scenes of activity for the functions that the space would provide for. These scenes were edited and combined to create the spaces. As we overlaid the scenes to create the interior layout, we introduced mixed levels to accommodate for a variety in program. The stepped form arrived at, bears resemblance to the tanada (棚田), the terraced rice fields of the region. There is a certain planned ambiguity in the spaces that allows users to create their own program from the space, a program that had not been specifically designed for or envisioned beforehand. Children from the elementary school across the street from the gallery enjoy playing in the gallery’s ambiguous white forms.

Thus, the gallery space created is more than just a “white cube” space. Its unconventional exhibition space has an effect on the way in which the artist will exhibit their work. The space can be used by the artist in their own way as it challenges them to take the space into consideration while planning an exhibition. This interaction with the space is an attempt to create spaces which are open to the characterization of its users, so the way in which it is used determines its use. And so, in turn, as the people characterize the space so the architecture characterizes the urban landscape.

Leave a Reply